Friday, March 07, 2025

As we integrate AI dev tools into our teams, I experimented by writing a desktop app in a language I have never used relying on LLM code generation. I primarily used Claude via web and API through aider, with some help on more generic Rust questions from Gemini Advanced.

The main areas for human intervention were

- tweaking imports and syntax, that weren’t worth the tokens,

- removing template code to get it to take user input,

- fixing the eventing to get messages sent from the UI to local the Ollama API,

- properly sharing state and using channels for realtime API to UI updates.

For some of these I’d manually intervene to get it on the right path then have it clean up. For others it probably would have figured it out with enough prompting direction, but it was easier for me to write the code than the prompts.

I have not tried this but if you’re looking for a proper macOS LLM GUI, Enchanted seems reasonable, but at time of writing last commit 4 months ago is a concern. Although it is Swift. I chose Rust with the goal of cross-platform, not sure if I will maintain this. See the code for a MacOS UI for Ollama GenAI models in Rust

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

Introduction to team-based care

Team-based care is a model of health care delivery where health professionals come together to provide comprehensive and coordinated care for a patient. Team-based care aims to improve the quality and continuity of care, increase efficiency, and reduce administrative burden by sharing health records and patient-centric workflows among health practitioners. In 2022, the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation awarded Ona with a grant to build a suite of FHIR-native digital health tools to accelerate team-based care in Indonesia. Led by the Summit Institute for Development (SID), who also received a grant from Grand Challenge Canada for team-based care, Ona has developed OpenSRP apps for midwives (BidanKu app), vaccinators (VaksinatorKu app), and community health workers (CHWs - KaderKu app)—using a standardized data model and shared database—to provide coordinated care for patients in communities and facilities across Indonesia.

Vision behind team-based care

For over a decade, SID and Ona have been applying technology to improve health care outcomes through the digitization of patient data and health care workflows, the integration of diagnostics and laboratory information systems, and the implementation / publication of impactful research and training methodologies. One pillar of our collaboration is to build out the plug-and-play suite of platforms and integrations needed to bring patient-centered team-based care to the communities where it can most significantly reduce mortality and morbidity. Rebuilding the OpenSRP product has allowed us to flexibly deliver apps purpose-built for the health worker teams that SID works alongside in Indonesia.

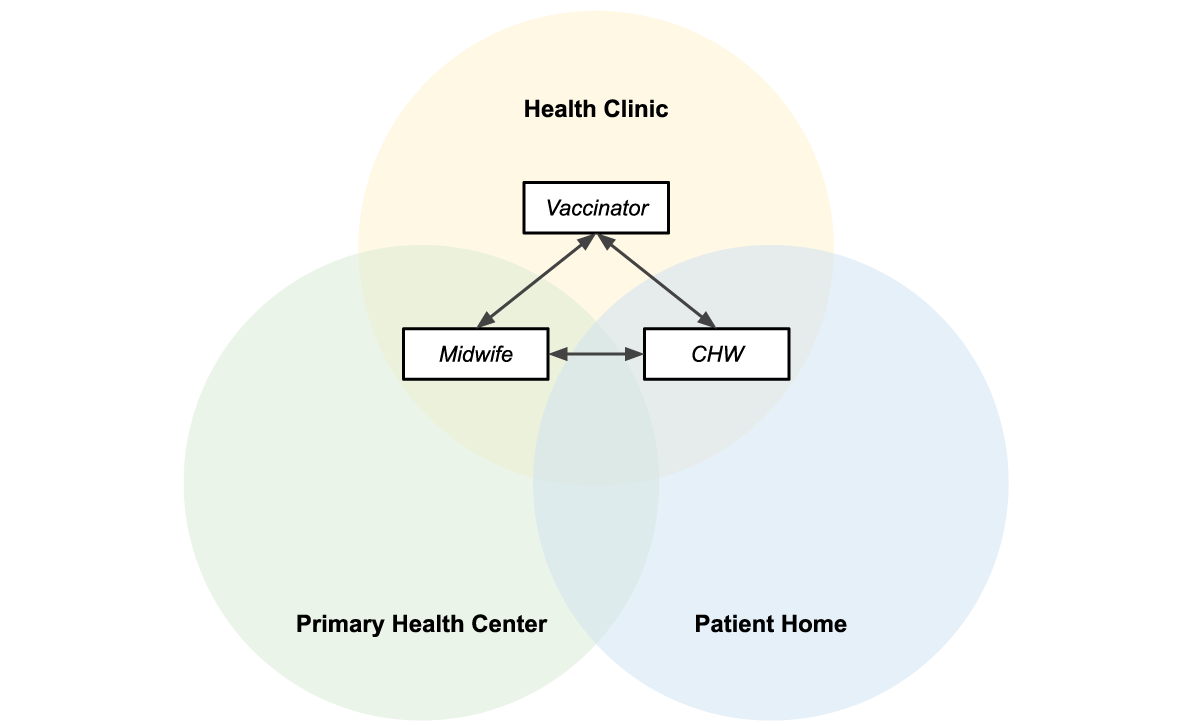

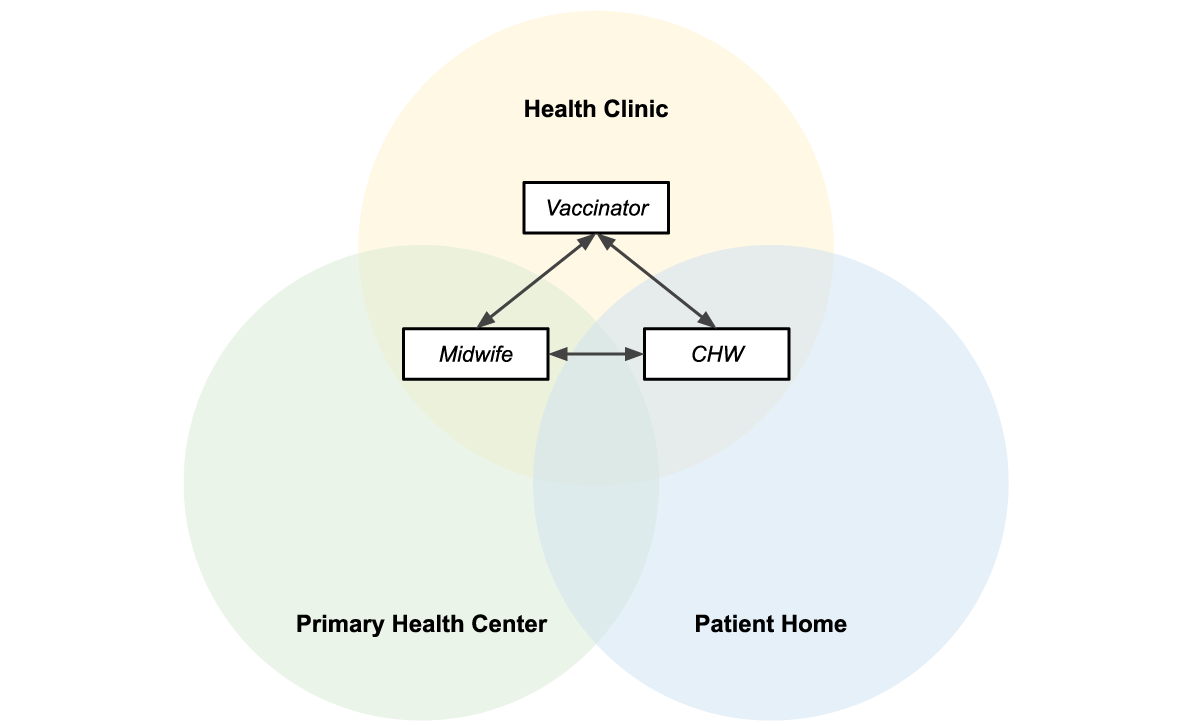

Collaboration between midwife, vaccinator, and CHW is essential to ensure patients receive high quality care. Midwives play a crucial role in providing antenatal care to pregnant mothers, in part by monitoring the health of the mother and baby during pregnancy. The midwife also assists the pregnant mother in delivery and provides postnatal care to both the mother and newborn. The vaccinator is responsible for administering the correct vaccinations to people from 0 to 18 years of age, and following the guidelines defined by the Indonesian Pediatric Society and required by the Indonesian Ministry of Health. The CHW is a community-based volunteer who cares for children, pregnant women, teenagers and the elderly. They provide education and counseling on nutrition, remind people to visit the Posyandu (these are community-based integrated health posts established for a day per month), and provide complementary food for pregnant women based on their nutritional status and the village policy.

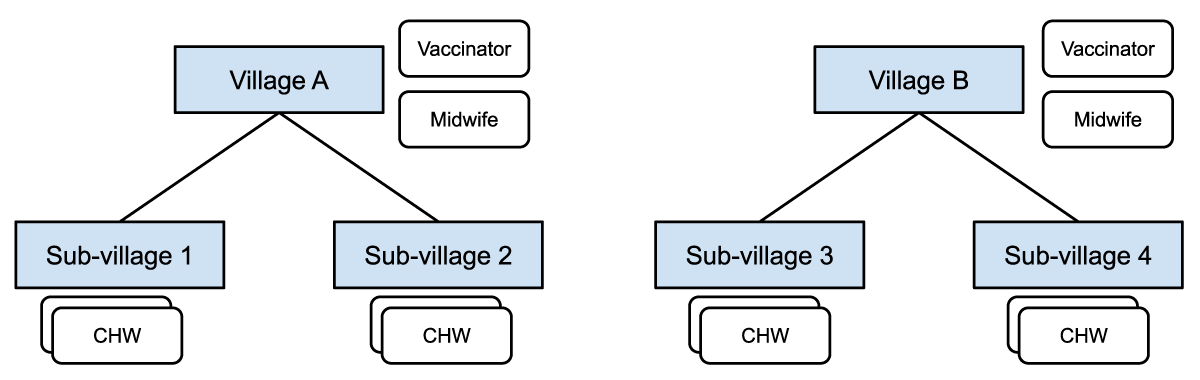

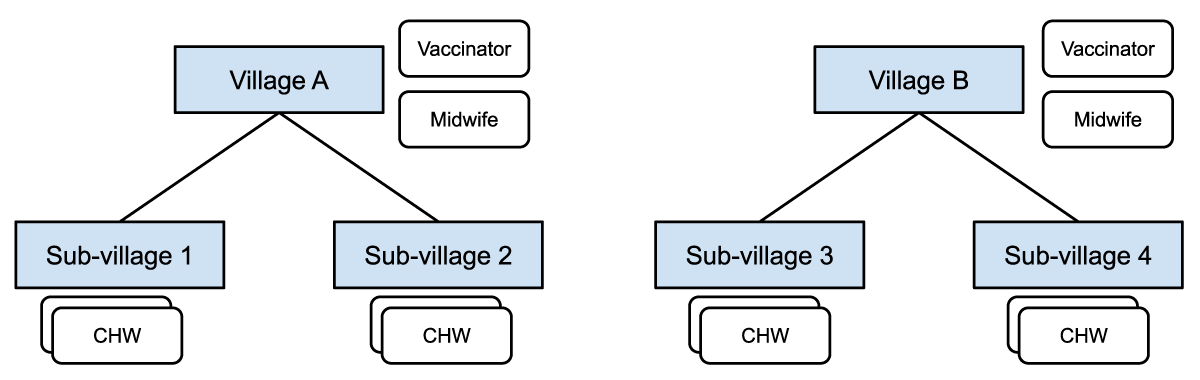

Figure 1: Midwives and vaccinators are assigned at the village level and responsible for patients in all the sub-villages. CHWs are assigned at the sub-village level and responsible for patients in a particular sub-village.

These frontline health care workers collaborate through:

- Information sharing: Midwives, vaccinators, and CHWs share information about pregnancies, births and immunizations in assigned locations.

- *Referrals: CHWs can refer patients (e.g. those needing ANC care, PNC follow up, assistance during delivery, or seeking follow up for minor illnesses) to midwives, and those seeking immunizations to a vaccinator or midwife.

Figure 1 shows how different healthcare workers are assigned at different levels in the administrative hierarchy, with access to different groups of patients in their respective villages or catchment areas.

Some of the challenges reported by health workers, government supervisors, and patients, when using the current health information system in Indonesia, include:

- Data quality challenges, such as data clumping, heaping, and other health record inaccuracies;

- Limited and slow access to health records, leading to delayed or unavailable data analysis;

- Non-synchronized data due to limited internet connection;

- When using paper records, risk of damage or loss of the records themselves;

- Limited or no ability to share data and communicate between systems;

- Data is for reporting only not for providing feedback to frontline workers, supervisors and community members nor for taking actions in a real time basis;

- Difficulty managing patients at scale. Health workers need to manage thousands of patients and schedule visits manually on paper, which has led to missed appointments for essential health services.

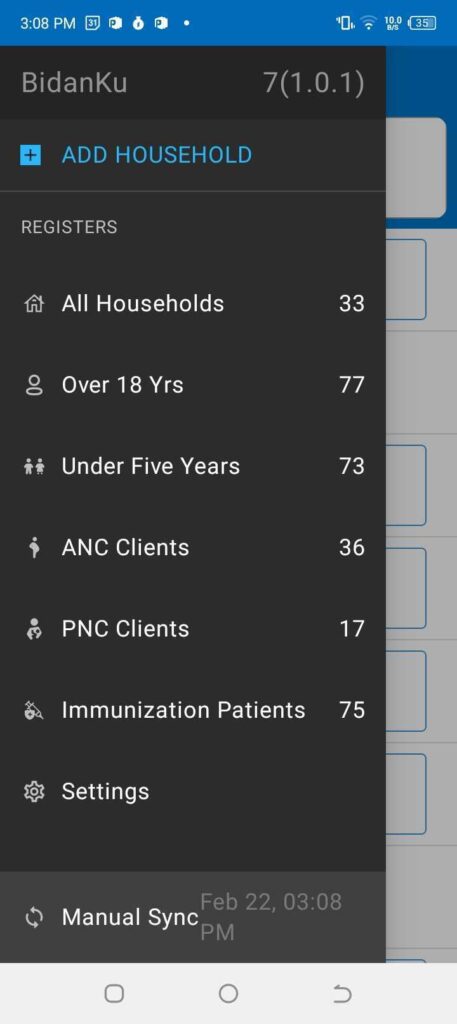

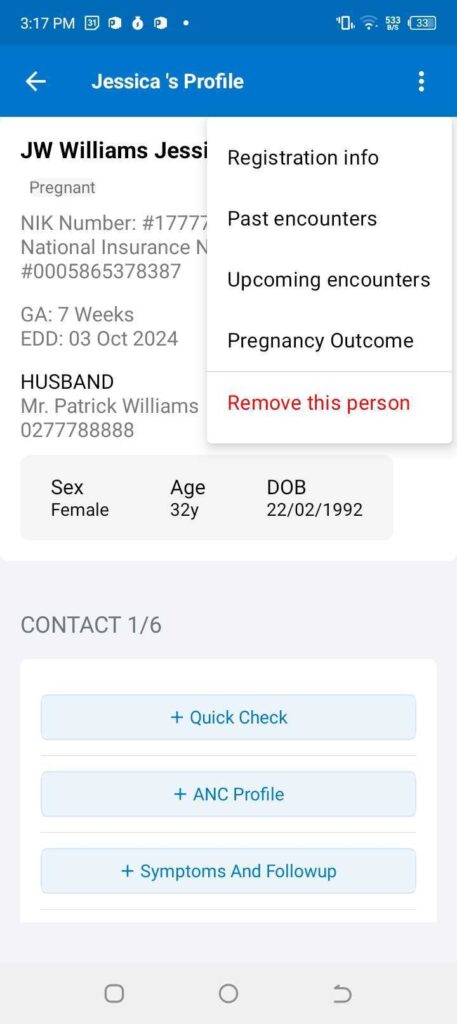

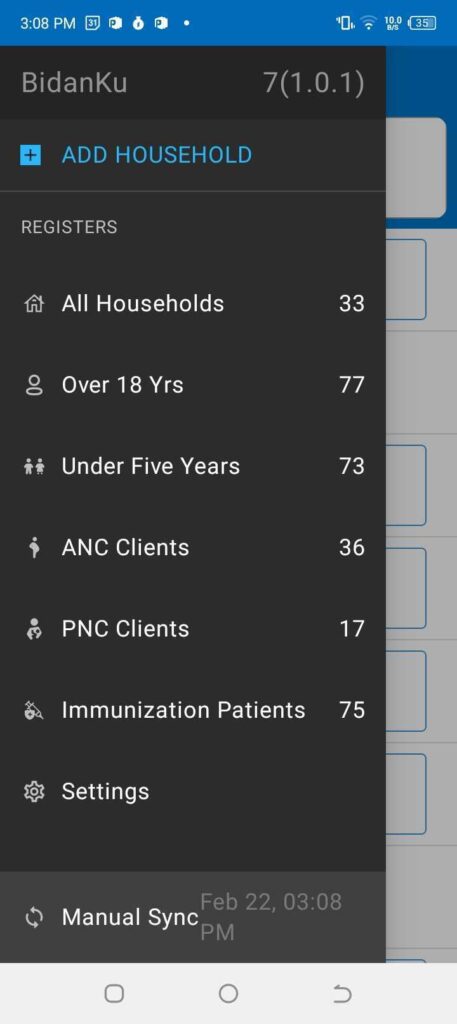

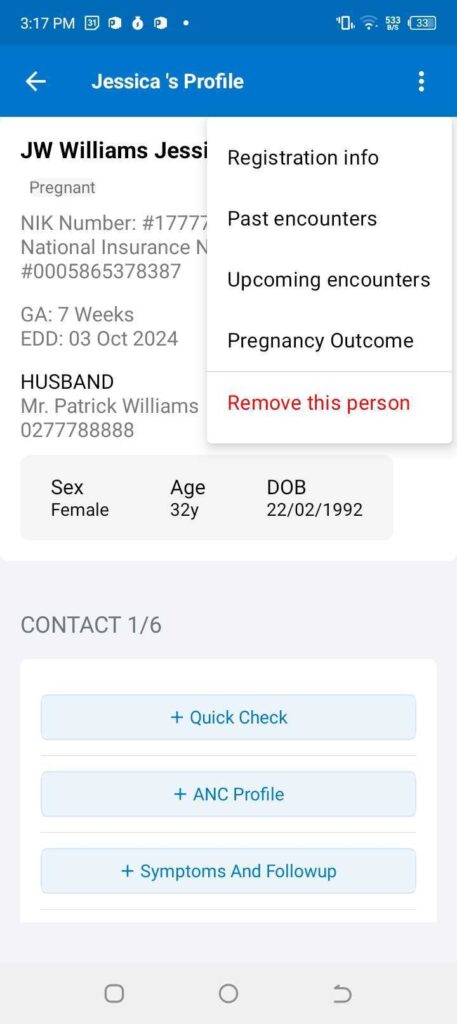

Figure 2: The left panel shows the main menu in the BidanKu app, where midwives can select the particular set of clients they are interested in viewing. The right panel shows the patient view for a synthetic patient and the dropdown menu with actions to take for that synthetic patient.

To address these challenges, SID and Ona developed three FHIR-native OpenSRP 2 apps that enable team-based care between three health care workers, later expanding to additional front line health care workers. The initial three apps are:

- BidanKu for midwives to use in primary health care centers and during Posyandu,

- VaksinatorKu for vaccinators to use during Posyandu and service delivery at primary care facilities (Puskesmas)s, and

- KaderKu for community health workers (CHWs) to use during Posyandu and in household visits.

Figure 3 shows how the three apps are used in overlapping locations that are part of the patients care journey.

Figure 3: Midwives, vaccinators, and CHWs operate in overlapping locations, making information sharing essential to providing efficient patient-centered care.

Shared data = patient centered care

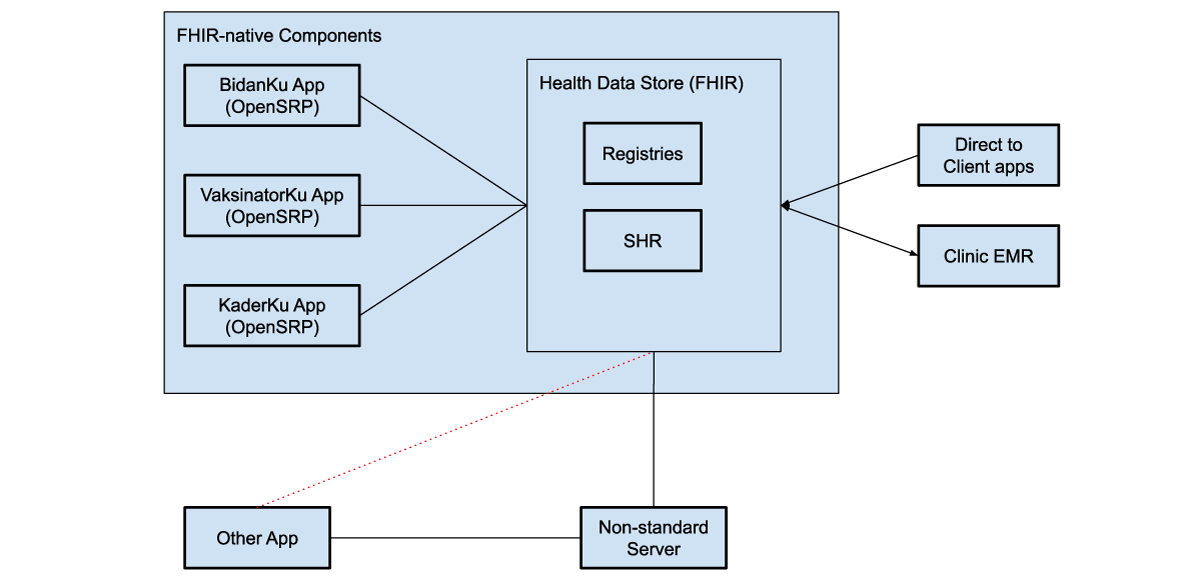

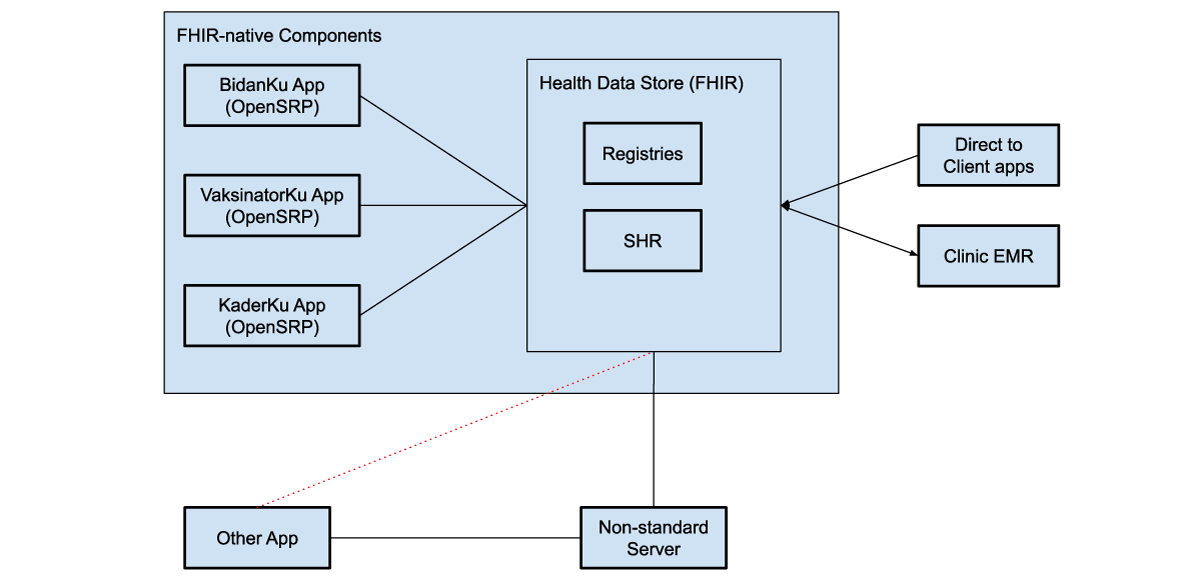

The three apps — BidanKu, VaksinatorKu, and KaderKu — all synchronize their transactional health data, such as patient records, and health workflow data, with the same health data store. This ensures that the most up to date data is synced to the health data store. If a health care worker is providing services to the same patient they can view the latest information on that patient.

Figure 4: FHIR-native components communicate directly with the health data store, which can be used to store shared health records (SHRs) as well as patient, facility, and other registries. These systems can use various intermediaries to communicate with additional external systems, both apps and clinical electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

The health data store can integrate with direct to client apps, through web apps, smartphone apps, or messaging platforms, like WhatsApp. For example, caregivers can fill in the details of sick child assessment forms from their phones at home, and then a midwife and CHW can access those assessments in OpenSRP 2 to view their symptoms, a preliminary diagnosis, and follow-up actions.

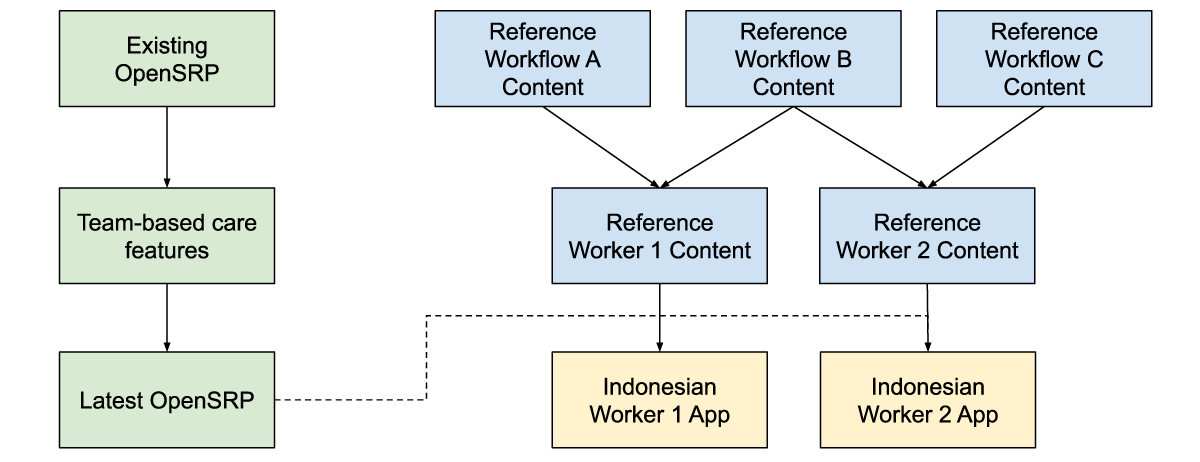

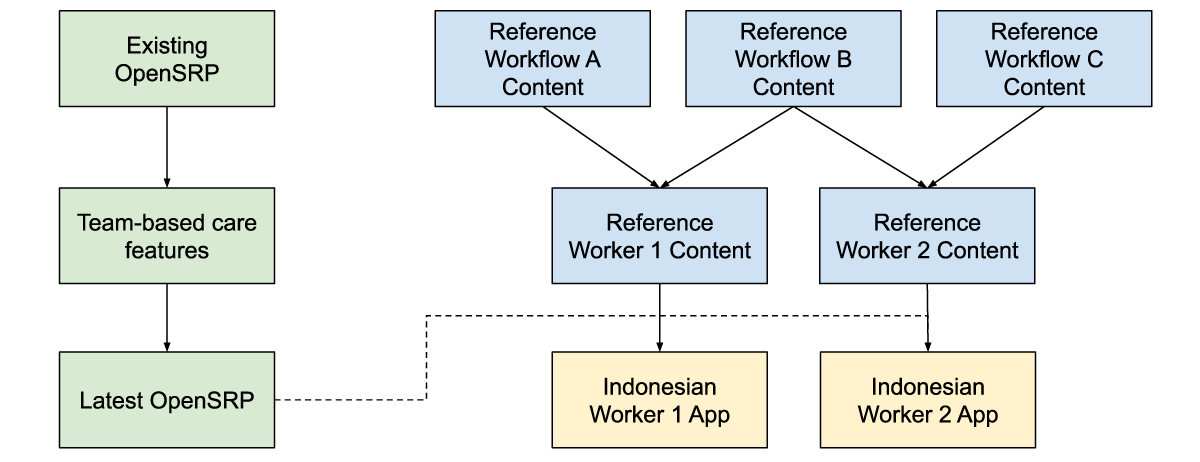

Each of these apps achieves their unique user-based functionality through configurations written in standards-based FHIR files. This gives us a well defined separation between the platform (OpenSRP 2) that runs the apps and the apps themselves. This allows SID, Ona, and future collaborators to continue working together to build additional apps tailored to more health care workers and related service providers, all of whom are essential to delivering unified team-based care at the community level.

The other unique separation of responsibilities, which we have implemented through OpenSRP 2 and demonstrated in this work, is between the apps and where health information is stored. Using an off-the-shelf FHIR store for health system data allows seamless interoperability between the apps and external systems that understand FHIR. This lets the apps function as different “views” of the data, instead of silos holding health vertical or worker specific information.

Figure 5: Reference workflow content, is combined with reference worker content and the latest app features to produce an app with the correct health workflow and worker content for the Indonesian context, while producing generic and reusable materials.

For at least the past decade, team-based care has been widely discussed in digital health, but to our knowledge it has never been deployed in a global health context supported by smartphone apps. Collaborating closely with SID, an experienced institution for health program implementation, as well as with the health care workforce members delivering care has allowed us to ground the features required for any team-based care platform in reality. Building on-top of a standards-based platform has allowed us to define the features and configurations required for team-based care in a way that goes beyond the specific location, health care workers, and health care workflows we are currently targeting.

Written in collaboration with:

Yuni Dwi Setiyawati

CEO, Summit Institute for Development

Edward Sutanto

DPhil Student, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford

Anuraj Shankar

Research fellow, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford

Monday, March 04, 2024

Ona created True Cover, a methodology and set of tools that combine high-resolution satellite imagery, spatial sample modeling methods, and lightweight mobile data collection, to enable health facility staff to more accurately calculate coverage for their catchment area. The type of coverage is flexible — it can be the coverage of up-to-date and fully immunized children or adults, mothers receiving fully antenatal care, the distribution of prophylactic malaria medications, or any other metric. This modeling technique lets health implementers use AI to target their services towards the poorly covered areas and households in their community that can benefit the most from increases in coverage.

Developing the True Cover algorithm

To develop True Cover, we talked to statistical sampling experts and spatial modelers in order to explore different approaches to this problem. We initially planned to use random cluster spatial sampling, an approach commonly used to fill in missing spatial data. In a previous partnership with a university research team, we had successfully used random cluster spatial sampling to conduct a national water point verification exercise with the government of Tanzania. However, while powerful in the hands of trained statisticians, this approach requires considerable expertise to interpret, and discipline in what data to collect and how to use it. Additionally, using data only from sample and replacement points limits the ability to benefit from the full set of coverage data collected.

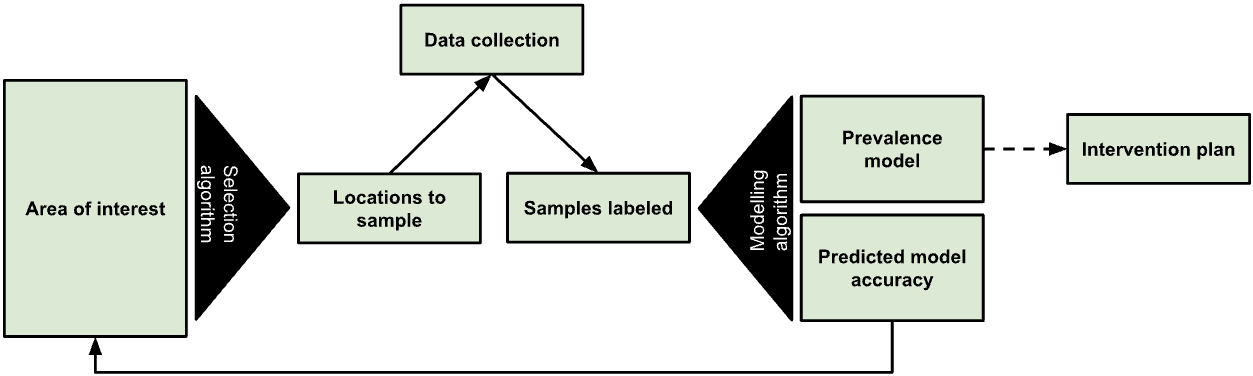

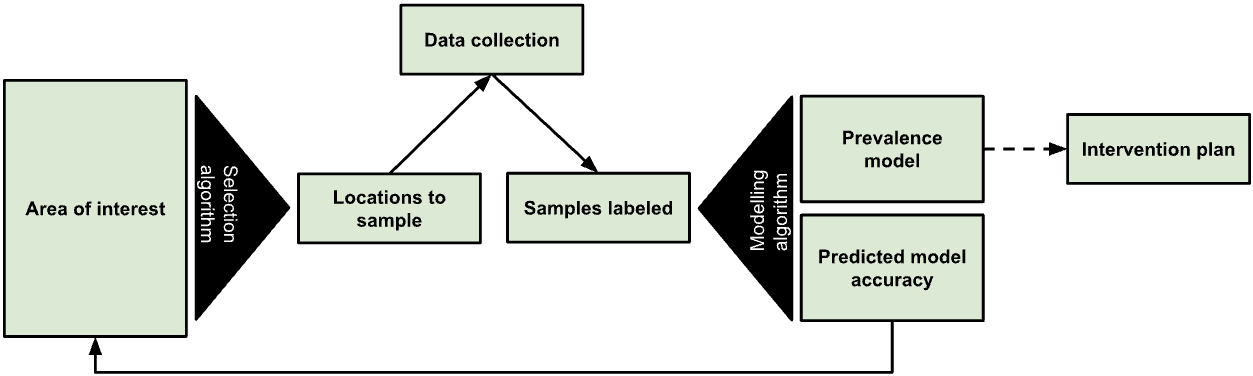

Figure 1: The True Cover algorithm chooses samples from an area of interest to collect data against, then based on the output model’s predicted accuracy recommends additional points to sample.

We expect that many local health teams would struggle to follow the rigor such an approach requires, and wanted to find an approach that let us leverage as much of the existing data as possible. In discussions with Dr. Hugh Sturrock, an epidemiologist at UCSF who we are collaborating with on malaria elimination work, we realized we could leverage a set of spatial modeling approaches he developed to help predict the prevalence of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and malaria in populations. Following these discussions, we partnered with Dr. Sturrock to develop, test, and create the True Cover algorithms and build a web service around them.

The True Cover algorithm works by taking as an input observations of service coverage at specific spatial locations (defined by a longitude and latitude tuple) and then predicting the coverage for that service across all structural points of interest that we expect people to live in within the target area. In the case of a local community, these are the locations of household structures. Advances in the availability of high resolution satellite imagery and machine learning based feature identification methods have made household structures available at the global scale. For example, in 2019 the Microsoft Bing team released 18 million building footprints in Uganda and Tanzania [1]. Over time we can expect to know where all people in a community live via satellite imagery, establishing an accurate and complete population to model and predict across. To make True Cover successful, we are bringing these two innovations together, then packaging and operationalizing them for use in the communities that can benefit most from them.

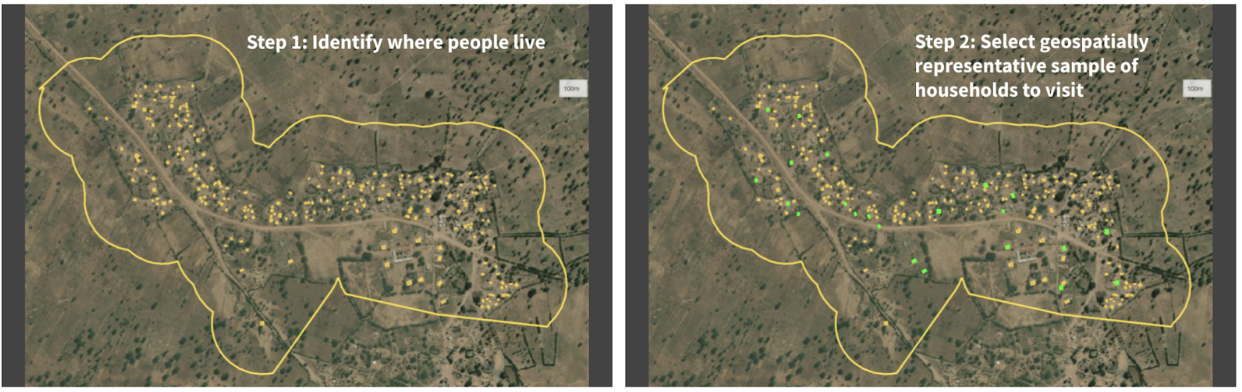

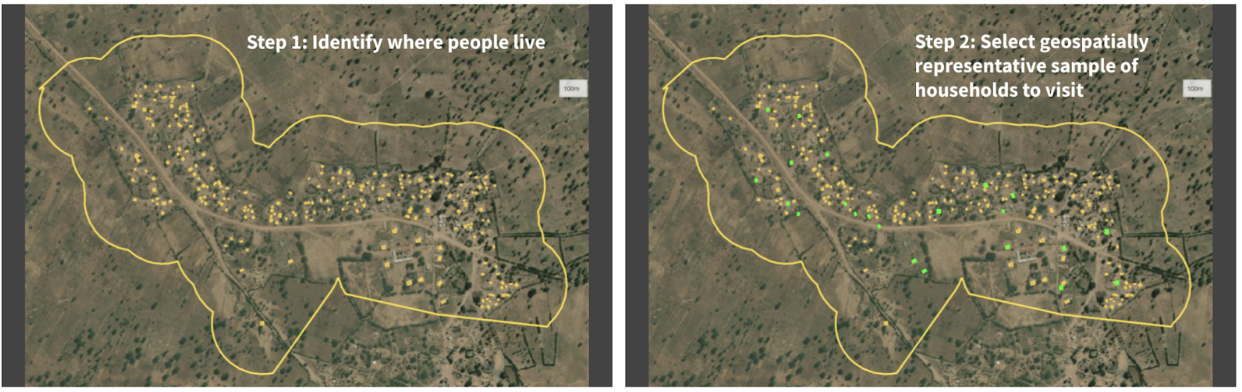

Figure 2: Given a set of unsampled points of interest (e.g. households) and a chosen geographical area (i.e. catchment area), the left panel shows all the households in that catchment area tagged for analysis. The right panel shows the True Cover algorithm selecting the set of households to sample, which it predicts will lead to the highest increase in prediction accuracy.

The resulting steps of the True Cover algorithm are:

GIVEN high resolution satellite imagery, OUTPUT household labels for where community members live,GIVEN household labels AND optional known data on households AND an adaptive spatial sampling method, OUTPUT a spatially distributed sample of households to collect data from,GIVEN coverage data on household labels, OUTPUT estimates and confidence for all households,GOTO STEP 2.

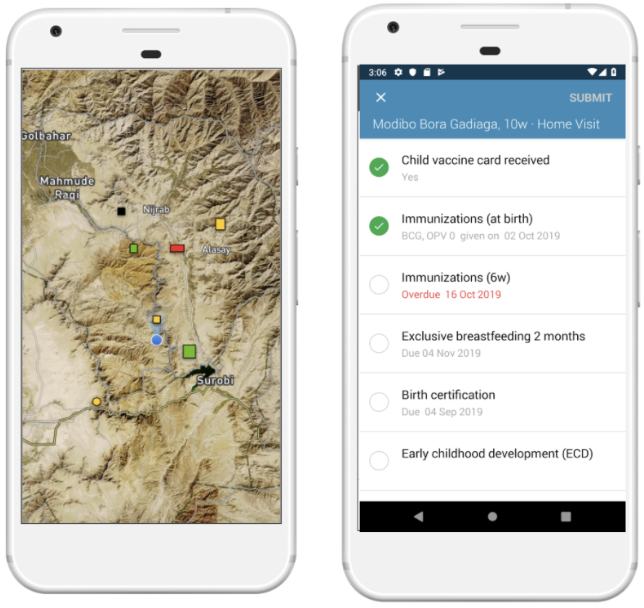

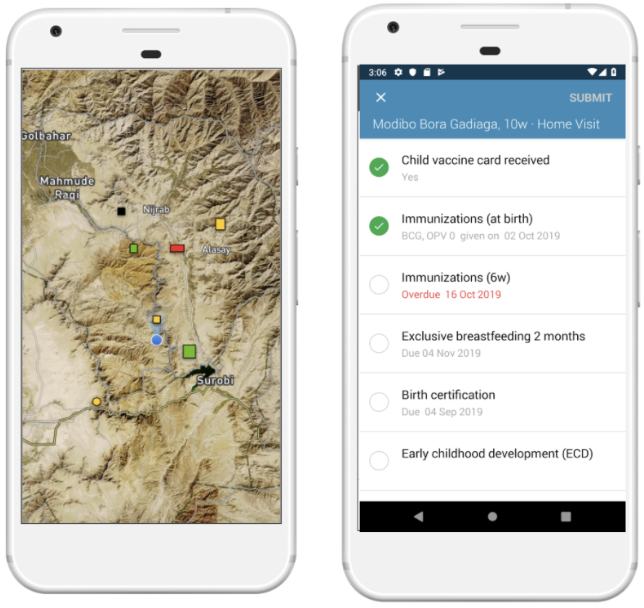

We then developed a task based data collection approach, on top of OpenSRP, to allow health workers to download and view all structures on a map and collect data on the structures they are assigned to visit. Using the OpenSRP app they can easily navigate to the house they are assigned to — indicated by color-coding the structure green — and collect data related to coverage. In the case of immunization, this is the number of children at the household who are up-to-date on their immunizations or fully immunized.

Figure 3: The OpenSRP 2 app shows POIs overlayed on high-resolution satellite imagery. OpenSRP 2 color-codes POIs to guide the user toward where to collect data and updates the color-coding based on users’ completed forms linked to POIs. All OpenSRP 2 configurations and data are FHIR-native.

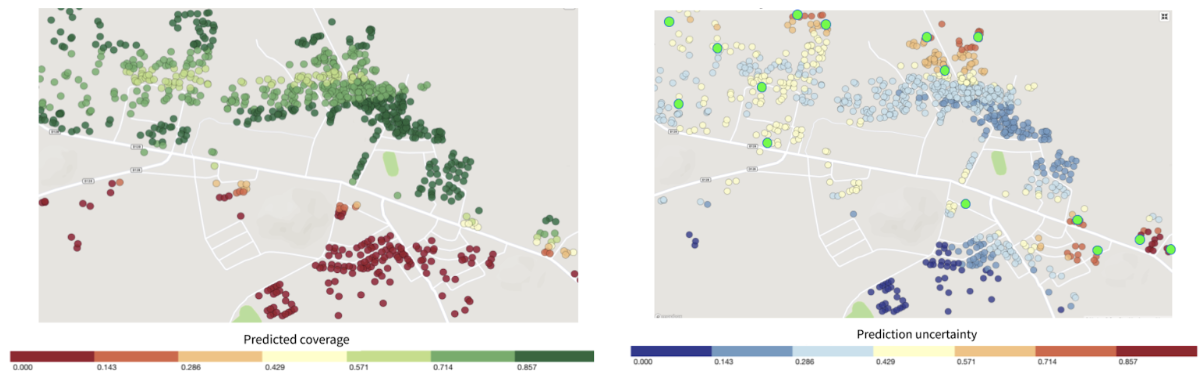

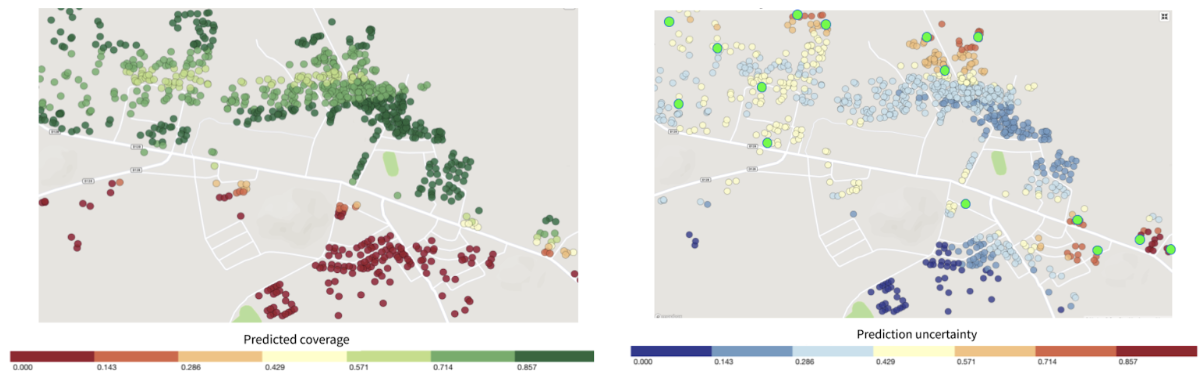

The collected observations are fed into True Cover, which combines these new observations with previously collected observations to update the predicted coverage across all structures in the community, both those with and without observations. When visualized, this produces an intuitive coverage map that makes it easy to identify problem areas. Because True Cover is an active learning model, the accuracy of its predictions improve as more observations are added.

Figure 4: Left panel shows structures color-coded by True Cover’s prediction of the likelihood of household members being fully immunized (coverage). Right panel shows those same structure color-coded by True Cover’s confidence in its coverage estimates.

One of its key features is True Cover’s ability to calculate the confidence of each prediction it makes. The right panel in Figure 4 shows both the areas where the model is able to predict with high confidence, and the areas where more data is needed to improve the prediction. The model’s confidence scores are an input to the adaptive sampling approach, which selects the locations to collect data from that will provide the greatest increase to the model’s overall predictive accuracy. This adaptive sampling approach is more efficient compared to random sampling because it requires less data collection to achieve an equivalent improvement in accuracy. Less data collection leads to greater impact, e.g. increase in vaccination coverage rates, with less time and money spent.

Validating True Cover

Our original goal was to field test the full True Cover methodology in a pilot site. However, we were unfortunately unable to due to delays in project site approval and the reprioritization of community efforts towards COVID-19 prevention through testing and vaccination. As a result, we found opportunities to validate the model across a number of different use cases with projects that could make their existing data available to us.

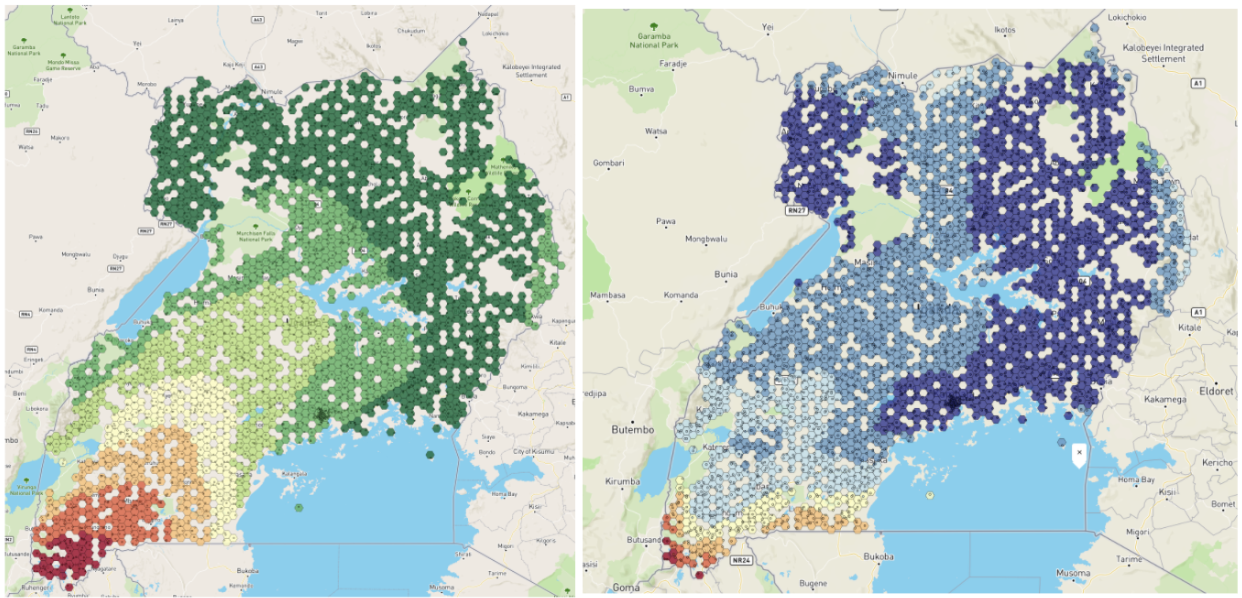

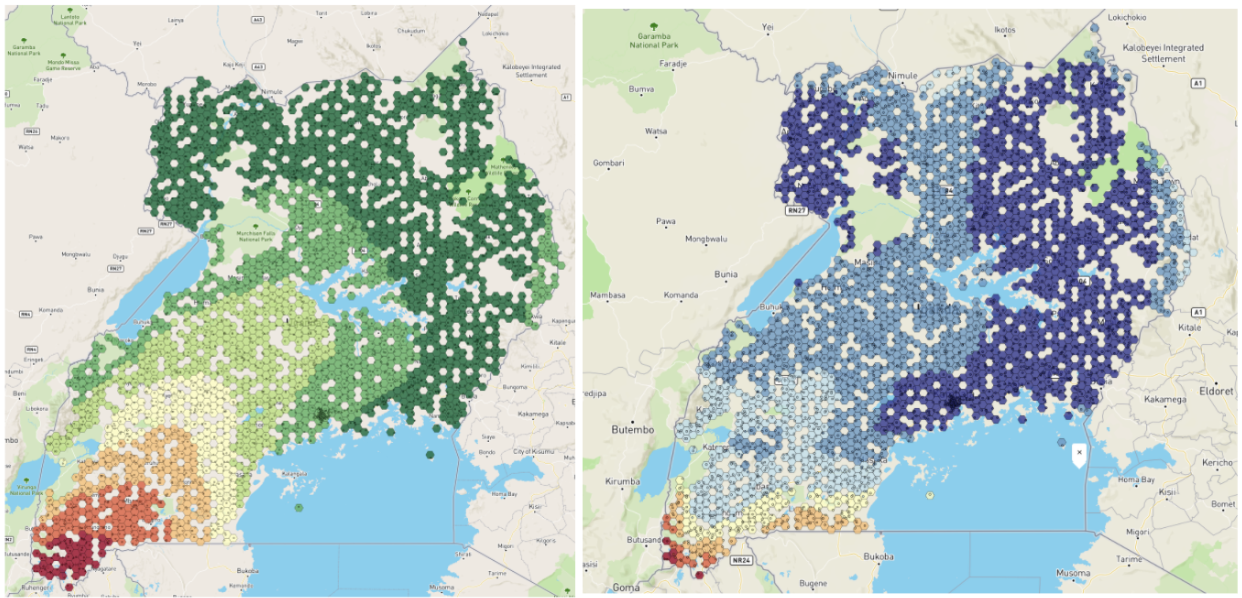

Figure 5: Left panel shows the BCG vaccination coverage estimates in Uganda generated by True Cover. Right panel shows confidence in BCG vaccination coverage estimates.

Using publically available Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) data we were able to generate a BCG coverage and confidence map for Uganda. This map shows lower coverage in south western Uganda up to the border, and generally lower confidence in the predictions along borders. This would align with demographic data showing that wealth is more concentrated in larger cities, such as Kampala, in central Uganda, and the sparser data available near the borders.

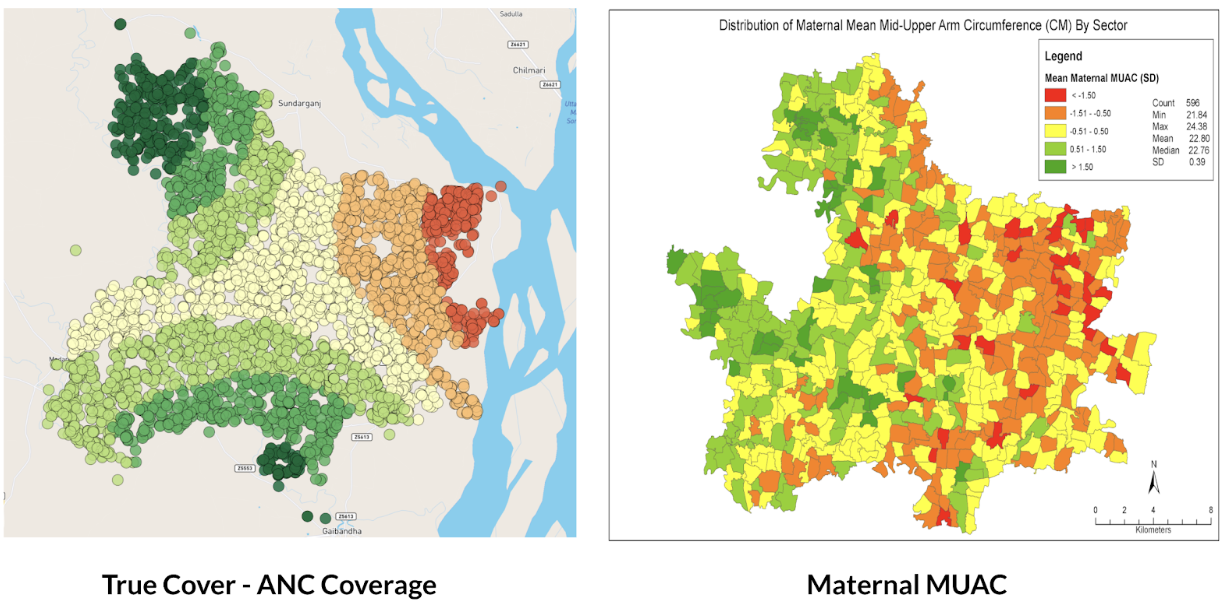

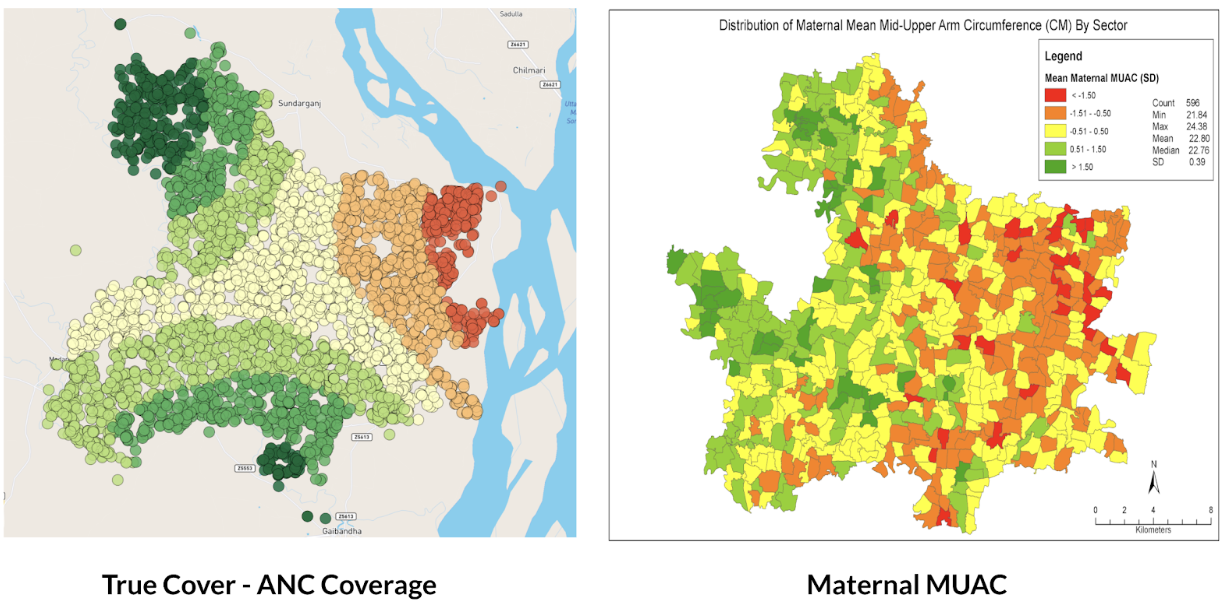

Working with a research partner in Bangladesh, we were able to use True Cover to predict antenatal care coverage rates, which interestingly were found to correspond with maternal middle upper arm circumference (MUAC) classifications from a different data source. This also shows the expected pattern of lower coverage rates closer to the Brahmaputra river, where people are more economically disadvantaged.

Figure 6: Left panel shows True Cover’s prediction of antenatal care coverage in the area studied in Bangladesh. Right panel shows the average maternal MUAC score aggregated by sector (the finest-grained administrative boundary) in the same area.

Why current approaches to measuring coverage fail

We set out to develop a methodology and set of supporting analytical and data collection tools that enable health teams to better visualize service coverage (e.g. immunization coverage) at the community level. Our goal with True Cover is to enable communities to develop strategies to improve health equity by helping them better understand where problems in their community lie.

True Cover addresses some of the challenges inherent in measuring and estimating coverage at the community level. Most methods of estimating service coverage rely on denominators based on target populations. As coverage rises, however, coverage estimates become increasingly sensitive to errors in target population estimates [2]. For example, a 10% error in the target population estimate of 90% coverage, would lead to a coverage range from 81% - 99% (because 10% of 90% equals 9%) whereas the corresponding error range when estimating at 50% coverage would be from 45% - 55%. Additionally, population estimates are largely based on five to ten year old census data and are often incorrect, sampled at too high an administrative level (e.g. district level), and are sensitive to factors like human migration, which is more prevalent in at-risk and marginalized communities.

To circumvent these denominator challenges, demographic and health surveys (DHS) and multiple indicator cluster surveys (MICS) are used. These methods are very expensive and are only able to provide an accurate snapshot of coverage once every several years. These surveys are sampled to provide accurate coverage estimates at national and sub-national levels (e.g. district or sub-district). If you are a nurse at a health facility, this will only provide a general sense of immunization coverage within their area. They will not know if local coverage is higher or lower over time, or be able to visualize the heterogeneity of coverage within their communities. Their ability to improve coverage is fundamentally a visibility problem. If we can empower them to see where in their community people are more likely to miss vaccinations, they can target those areas and improve coverage.

Applying True Cover to save lives

With True Cover we have successfully built the technical foundations to generate on demand predictive coverage maps capable of playing an active role in guiding vaccination, resource distribution, and other campaigns. This integrates with the OpenSRP 2 app’s task-based data collection approach, which links tasks to household structures and has been successfully used to coordinate the spraying of hundreds of thousands of homes during indoor residual spraying (IRS) campaigns. Further field testing of the system is required to demonstrate True Cover’s value with campaign based apps and validate the effectiveness and utility of the True Cover approach to estimating coverage.

That said, our partners have already found the predicative coverage maps generated by True Cover useful in their decision making. One of our research partners in Bangladesh has used True Cover to spur important discussions, including programmatic changes. While we wish we had been able to go further to validate this approach, we are excited to see that the ability to spatially sample points using the True Cover algorithm has proven useful on its own.

As the frequency of geospatial monitoring and the power of spatial machine learning continue to increase, we are increasingly convinced in the underlying value of the Ture Cover.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible with the support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Johnson and Johnson, and the Goldsmith Foundation.

References

- Microsoft releases 18M building footprints in Uganda and Tanzania to enable AI Assisted Mapping

- Assessing the quality and accuracy of national immunization program reported target population estimates from 2000 to 2016

Friday, October 27, 2023

Digital health works exactly as it was designed and that’s the problem

In a recent article in the Journal of Global Health, Karamagi et al. describe digital health as in a state of e-Chaos. They demand digital health projects “stop further duplication, [and instead] encourage interventions that holistically strengthen the health systems.” Despite remarkable progress in digital health, we believe the industry faces significant obstacles to greater impact if we continue with business as usual — and instead propose a holistic solution built around the FHIR standard.

What’s broken with digital health?

In digital health’s long history of projects, technical and implementation choices have been pragmatic, guided by (1) available technology, (2) implementation-specific requirements such as “must work offline”, and (3) per-project funding. While some projects have successfully solved important problems and created measurable impact, nice-to-have goals such as interoperability and reusable content were unfulfilled and health challenges remained unsolved at a health systems level.

Several of our projects worked like this: a group focusing on improving childhood immunizations through community health workers wants a mobile app. However, in practice, immunizations were discovered to be covered by several other touchpoints such as health facilities and campaigns from special interest NGOs, with each group using their own software. Unsurprisingly, we would be asked to send and receive data from these other systems and these requests would be treated as “integration features” — just another requirement added during the development process. Sound familiar?

This common scenario means maintaining interoperability requires each new system to integrate with every existing system, leading to an exponential increase in effort and cost, which makes large-scale interoperability infeasible. To combat this, the digital health community has coalesced around two solutions: hubs and monoliths.

Hubs and Monoliths: a little better than building integration features

Integration hubs are platforms meant to connect different systems. Tools such as OpenHIM address this specifically for health, while data integration tools like Airbyte, Beam, NiFi, and OpenFN are for generic use cases. Instead of integrating one program’s solution to another’s, they both integrate with the hub, which is an improvement but comes with its own challenges. Each program-to-hub integration still requires additional integration work, and for other solutions to benefit, they must also integrate to the same hub. Hubs also face a “cold start problem.” If no other program has connected to the integration hub, why bother connecting this program. Since future benefits are unknown and there is no immediate payoff, this is usually the first type of scope to be cut.

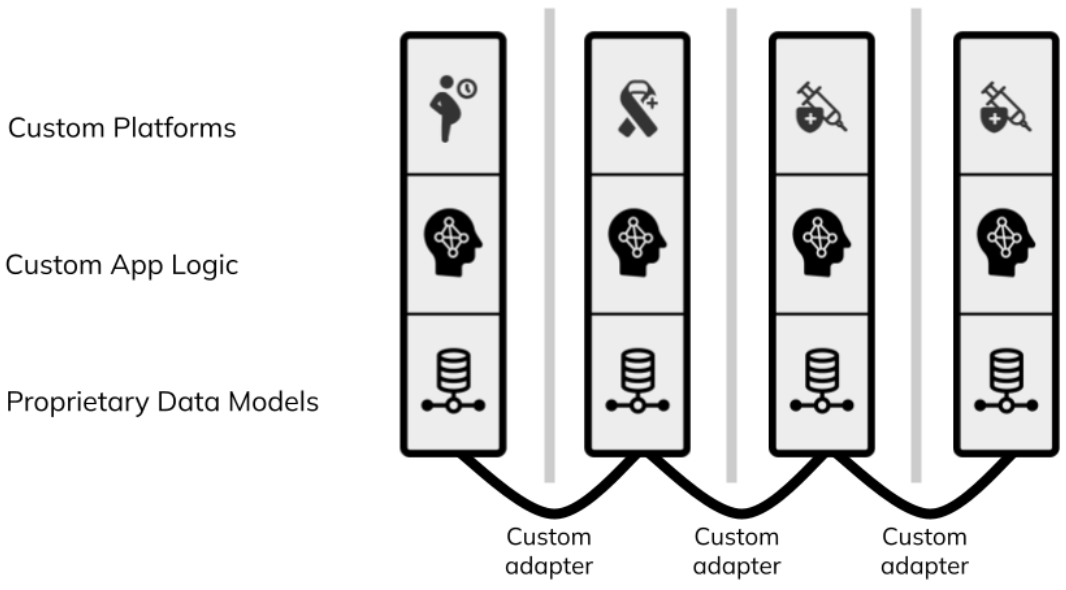

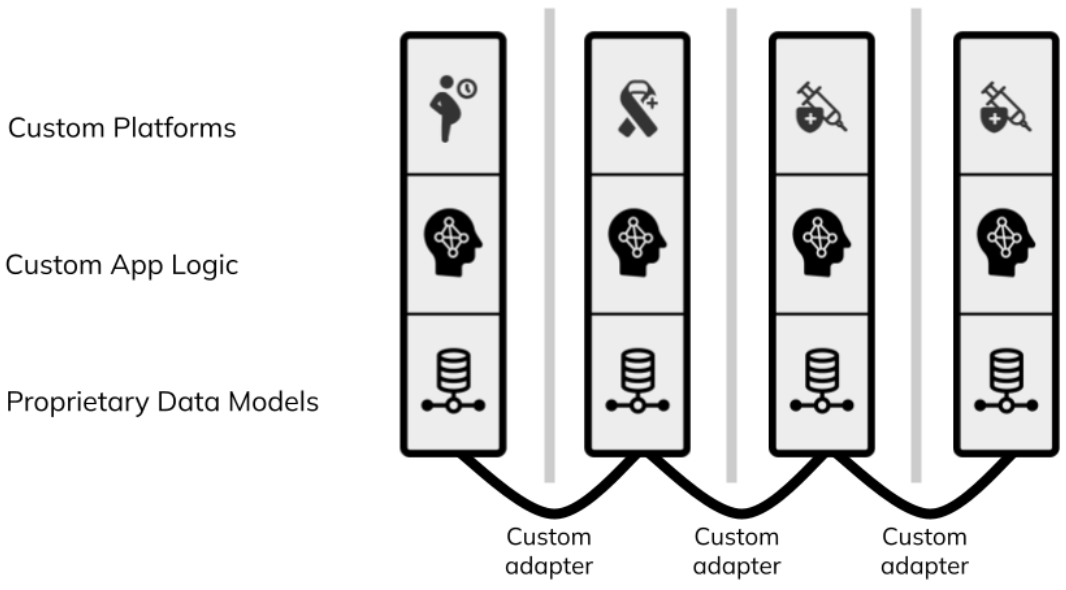

Monolithic interoperability is the approach of using a single platform (often with a proprietary data and workflow format) for every app and system component. This works for single projects in isolation, however because of the myriad of features required to scale – from supply chain to civil registration – you cannot build a health system on a single application. Even still, having two programs run the same platform does not ensure they are integrated, leading again to siloed and overlapping systems. Figure 1 below shows the siloed health system architectures that we end up with today using direct integration, the hub, or the monolith approach.

Figure 1: each column represents a different digital health program. Traditional digital health architecture is siloed and requires custom adapters that are often never built.

FHIR = better than hubs and monoliths

Hub and monolith architectures have led to digital health solutions that are not designed to address health challenges from a health systems standpoint, which makes sense since they were designed to solve problems from a project-perspective. What is missing is not to add an integration feature, an integration hub, or a monolithic solution, but to have integration between facility and the community apps be unavoidable, out-of-the-box, and by default without additional effort or cost. Sounds impossible?

Thankfully the global health standards community has already done a lot of the work. To break down the silos and move forward we need to use platforms and tools that build around a common architecture where integration is not something to be added but a given — built into the system itself. The FHIR standard provides that architecture.

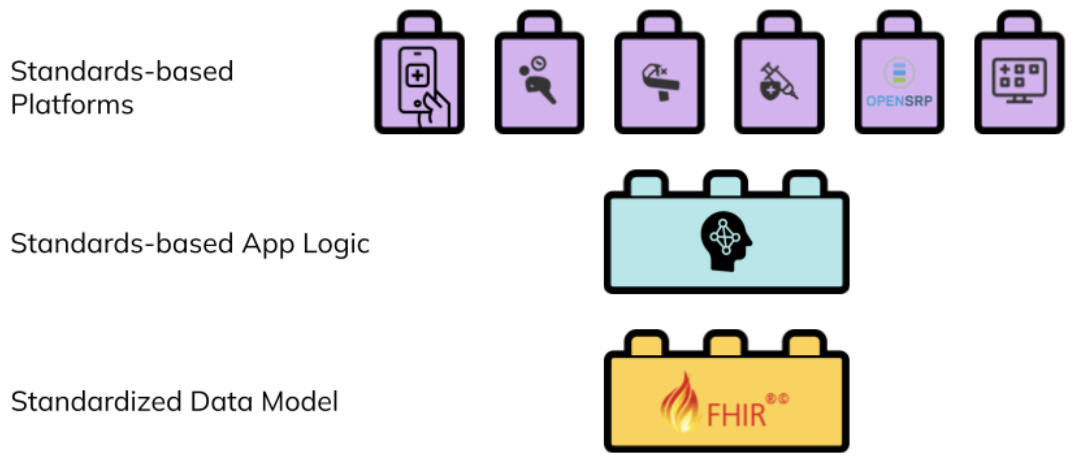

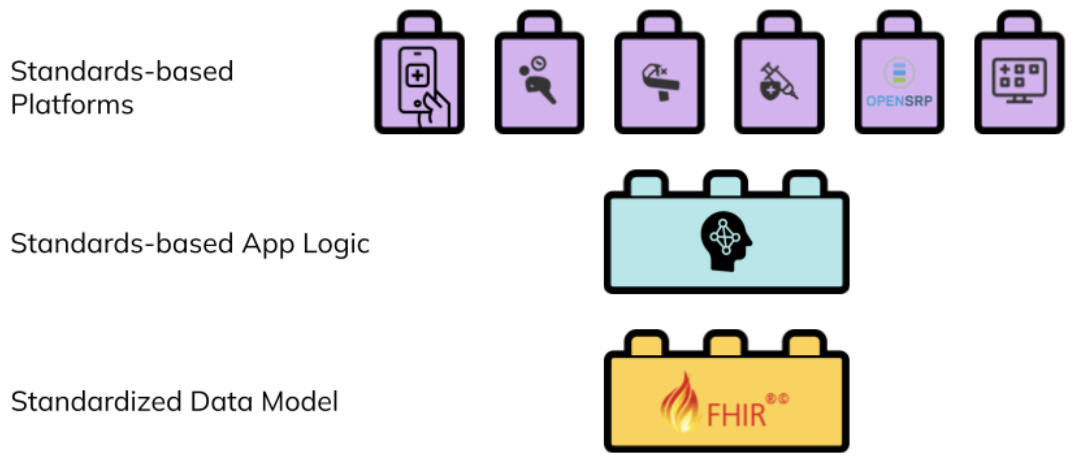

HL7 FHIR, the globally recognized health data and workflow standard, provides the opportunity to create a new generation of digital health systems that overcome traditional interoperability challenges. FHIR can represent both the app’s logic and underlying data model. With recently added mobile support, through Google’s Open Health Stack, FHIR provides a fundamentally new type of architecture built around a common shared data model that puts interoperability at its core.

Figure 2: a standards-based digital health architecture combines reusable building blocks based on a common standard.</p>

Interventions can create reusable FHIR content to describe the healthcare workers, healthcare workflows, and their connections, and contribute to an evolving ecosystem of innovation that does not depend on the specific organization or tools used in the implementation. Any platform that understands FHIR can load that intervention and its generated data, integrate it with other FHIR data or systems, and execute it.

Figure 2: a standards-based digital health architecture combines reusable building blocks based on a common standard.</p>

Interventions can create reusable FHIR content to describe the healthcare workers, healthcare workflows, and their connections, and contribute to an evolving ecosystem of innovation that does not depend on the specific organization or tools used in the implementation. Any platform that understands FHIR can load that intervention and its generated data, integrate it with other FHIR data or systems, and execute it.

FHIR gives us coordination by default

While hubs and monoliths have led to “unintentional and extreme duplication of digital tools which implies a lack of a coordinated approach and weak partnerships” (Karamgi et al.), FHIR avoids this by making standards-based interoperability a prerequisite.

Consider a ministry of health working with partner organizations to implement a program for the prevention of mother to child HIV transmission. One organization may have an app for maternal health, such as antenatal care visits, while a second organization has their own app for HIV management. To limit the risk of mother to child transmission these apps need to work together. Let’s take a look at how to integrate this data under the 3 solutions we’ve discussed:

- With the hub approach, an integration hub is set up that both programs have to be aware of and have access to; then these programs must create or implement connections to that hub. The programs must also agree on a common language for the information they want to share.

- In the monolith approach, the programs use the same proprietary platform, and then they must either integrate the data of one program completely with the other or write an integration that continuously synchronizes data between the two systems. To have a useful integration they will still need to ensure that both systems represent information in the same way.

- With a standards-based approach, where both programs store their data in FHIR, the different programs are alternative ways to view and manage the same underlying shared health records. There’s one FHIR server set up and both programs can query and push data into it.

Figure 3: a facility app used by a nurse, and a community app used by a community health worker, are alternative ways to view, manage, and contribute to the same set of shared health records.</p>

One way to think of a FHIR health systems architecture is as a set of interlocking tiles that connect because of, not in spite of, their structure. Like Lego pieces, they are built to be interoperable with each other. Programs and countries that are adopting FHIR-native platforms can add on new modules over time, and be confident that their data integrates with other FHIR tools.

Figure 3: a facility app used by a nurse, and a community app used by a community health worker, are alternative ways to view, manage, and contribute to the same set of shared health records.</p>

One way to think of a FHIR health systems architecture is as a set of interlocking tiles that connect because of, not in spite of, their structure. Like Lego pieces, they are built to be interoperable with each other. Programs and countries that are adopting FHIR-native platforms can add on new modules over time, and be confident that their data integrates with other FHIR tools.

Packaging FHIR for sustainable impact

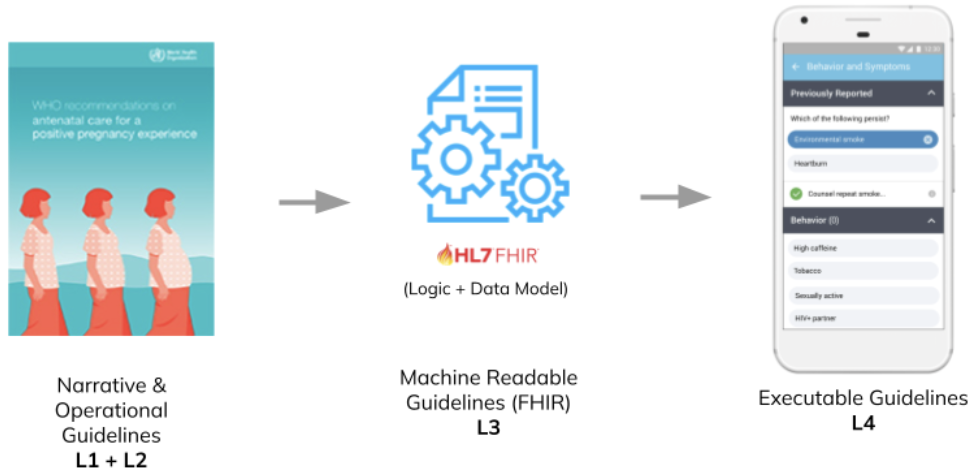

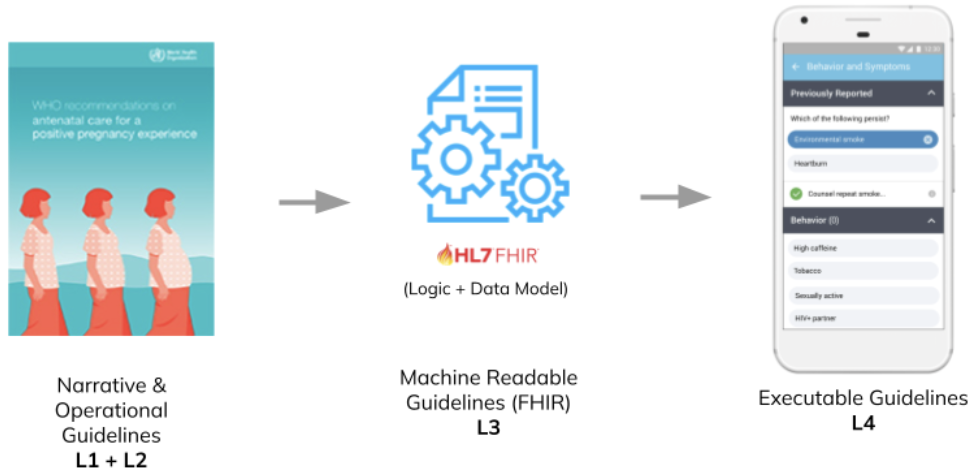

By transitioning to digital health architectures built around standard based systems that can store a shared health record for each client that interacts with the healthcare system, programs and countries open the door to standard packages of reusable content. For example, the SMART Immunization Guidelines created by the WHO, or the Antenatal Care SMART Guidelines implemented in OpenSRP, are computable – or “machine readable” — healthcare guidelines that can be run on any application that can interpret and execute FHIR, as depicted below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: the SMART Guidelines provide a standards-based common language for building reusable healthcare workflows that can be combined like Lego pieces.</p>

Organizations running digital health programs, and the countries implementing them contribute to the growing set of computable health packages, all defined in the same FHIR-based format. These packages are plug-and-play. If a program is running a FHIR-based electronic immunization register in their primary healthcare facilities, when they want to expand it to community outreach they don’t need to transfer any data, they simply point their FHIR-native community app at the same shared health records they are using in their primary healthcare facilities.

Figure 4: the SMART Guidelines provide a standards-based common language for building reusable healthcare workflows that can be combined like Lego pieces.</p>

Organizations running digital health programs, and the countries implementing them contribute to the growing set of computable health packages, all defined in the same FHIR-based format. These packages are plug-and-play. If a program is running a FHIR-based electronic immunization register in their primary healthcare facilities, when they want to expand it to community outreach they don’t need to transfer any data, they simply point their FHIR-native community app at the same shared health records they are using in their primary healthcare facilities.

There are many challenges leading to the current “e-Chaos” holding back digital health interventions. However, with FHIR, the SMART Guidelines, and community-driven global goods, we have all the tools, concepts, and architectures we need to reduce that chaos. The critical next step in this journey is to move beyond digitizing health apps to digitizing the health systems that those apps exist within.

Monday, June 19, 2023

Last week we had the pleasure of presenting on OpenSRP in Liberia at FHIR DevDays 2023. We received great questions and a lot of interest in our work build and deploying an Android-based FHIR application to real world users.

Take a look at the slides we presented below.

Figure 2: a standards-based digital health architecture combines reusable building blocks based on a common standard.</p>

Interventions can create reusable FHIR content to describe the healthcare workers, healthcare workflows, and their connections, and contribute to an evolving ecosystem of innovation that does not depend on the specific organization or tools used in the implementation. Any platform that understands FHIR can load that intervention and its generated data, integrate it with other FHIR data or systems, and execute it.

Figure 2: a standards-based digital health architecture combines reusable building blocks based on a common standard.</p>

Interventions can create reusable FHIR content to describe the healthcare workers, healthcare workflows, and their connections, and contribute to an evolving ecosystem of innovation that does not depend on the specific organization or tools used in the implementation. Any platform that understands FHIR can load that intervention and its generated data, integrate it with other FHIR data or systems, and execute it. Figure 3: a facility app used by a nurse, and a community app used by a community health worker, are alternative ways to view, manage, and contribute to the same set of shared health records.</p>

One way to think of a FHIR health systems architecture is as a set of interlocking tiles that connect because of, not in spite of, their structure. Like Lego pieces, they are built to be interoperable with each other. Programs and countries that are adopting FHIR-native platforms can add on new modules over time, and be confident that their data integrates with other FHIR tools.

Figure 3: a facility app used by a nurse, and a community app used by a community health worker, are alternative ways to view, manage, and contribute to the same set of shared health records.</p>

One way to think of a FHIR health systems architecture is as a set of interlocking tiles that connect because of, not in spite of, their structure. Like Lego pieces, they are built to be interoperable with each other. Programs and countries that are adopting FHIR-native platforms can add on new modules over time, and be confident that their data integrates with other FHIR tools. Figure 4: the SMART Guidelines provide a standards-based common language for building reusable healthcare workflows that can be combined like Lego pieces.</p>

Organizations running digital health programs, and the countries implementing them contribute to the growing set of computable health packages, all defined in the same FHIR-based format. These packages are plug-and-play. If a program is running a FHIR-based electronic immunization register in their primary healthcare facilities, when they want to expand it to community outreach they don’t need to transfer any data, they simply point their FHIR-native community app at the same shared health records they are using in their primary healthcare facilities.

Figure 4: the SMART Guidelines provide a standards-based common language for building reusable healthcare workflows that can be combined like Lego pieces.</p>

Organizations running digital health programs, and the countries implementing them contribute to the growing set of computable health packages, all defined in the same FHIR-based format. These packages are plug-and-play. If a program is running a FHIR-based electronic immunization register in their primary healthcare facilities, when they want to expand it to community outreach they don’t need to transfer any data, they simply point their FHIR-native community app at the same shared health records they are using in their primary healthcare facilities.